-

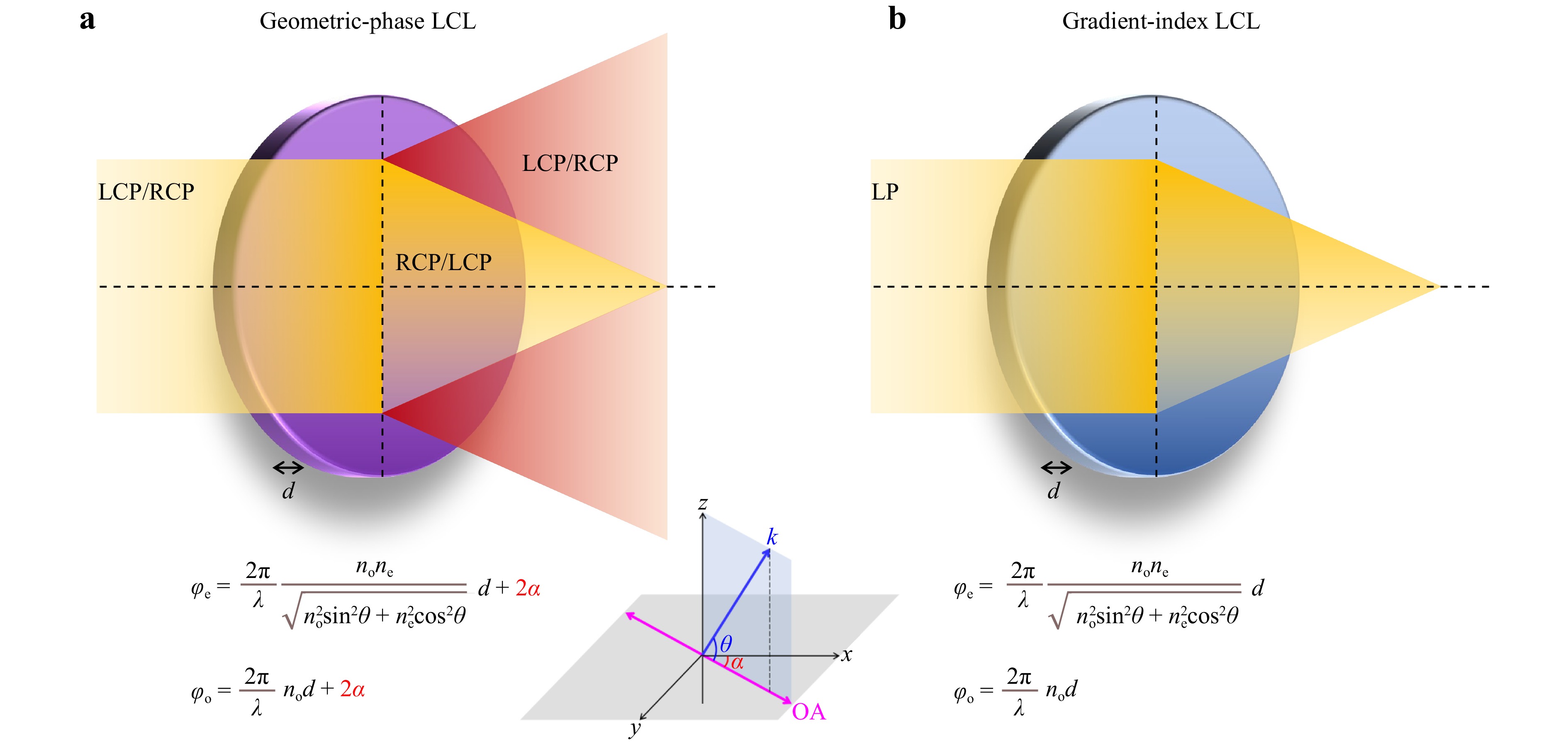

Geometric-phase (GP) liquid crystal lenses (LCLs)1–3, also known as Pancharatnam-Berry phase liquid crystal (LC) lenses, are composed of a layer of LC, whose molecular orientations are patterned to produce a lens-like phase profile. Gradient-index (GI) LCLs4–6 are also composed of a layer of LC, whose refractive index changes gradually across its volume. In the literal meaning, the former emphasizes orientation, while the latter refractive index. As LC is an anisotropic material, its refractive index is linked to its orientation. It appears that the two terms can be used interchangeably. However, as shown in Fig. 1, there is a fundamental difference in the way they modulate phase. For GI LCLs, the phase shifts φ of ordinary and extraordinary waves are purely propagation phases, which can be written as7

Fig. 1 Principle of a geometric-phase LCL and b gradient-index LCL. LCP: left-handed circular polarization. RCP: right-handed circular polarization. LP: linear polarization. φo/e: phase shift of ordinary/extraordinary wave. k: wavevector. d: thickness. θ: angle between wavevector and OA of LC. α: angle between OA of LC at a specific reference point (not shown or x-axis) and that at a target point (shown).

$$ {\varphi }_{o}=\frac{2{\text π}}{\lambda }{n}_{o}d $$ (1) and

$$ {\varphi }_{e}=\frac{2{\text π}}{\lambda }\frac{{n}_{o}{n}_{e}}{\sqrt{{n}_{o}^{2}{sin}^{2}\theta +{n}_{e}^{2}{cos}^{2}\theta }}d $$ (2) respectively, where λ is the wavelength, no/ne the ordinary/extraordinary refractive index, d the thickness, and θ the angle between the wavevector and the crystal or optic axis (OA) of LC. For GP LCLs, under certain conditions, when the incident polarization is circular and the phase retardation equals an odd multiple of half a wavelength2, the phase shifts φ of ordinary and extraordinary waves will become

$$ {\varphi }_{o}=\frac{2{\text π}}{\lambda }{n}_{o}d+2\alpha $$ (3) and

$$ {\varphi }_{e}=\frac{2{\text π}}{\lambda }\frac{{n}_{o}{n}_{e}}{\sqrt{{n}_{o}^{2}{sin}^{2}\theta +{n}_{e}^{2}{cos}^{2}\theta }}d+2\alpha $$ (4) respectively, where α is the angle between the OA of LC at a specific reference point and that at a target point, and the common second term 2α is called geometric phase. Since the geometric phase is a coincidental byproduct of Jones matrix operations8, from a mathematical perspective, GP LCLs are supposed to be way more susceptible to variations in polarization and retardation than GI LCLs.

According to Web of Science’s science citation index expanded database, from 2023 to 2025, 315 regular and review articles were published under the topic of LCL, of which 23 and 10 are related to GP and GI, respectively. Obviously, GP is more actively researched than GI. Among them, 6 are selected to represent the major breakthroughs in this field. In May 2023, Aishwaryadev Banerjee et al. (University of Utah) reported a varifocal Fresnel-type GI LCL for the application of smart contact lenses9. In September 2023, Prof. Shin-Tson Wu et al. (University of Central Florida) proposed to combine a broadband GP LCL, a half-wave plate, and a red-blue GP LCL to cancel out the chromatic dispersion10. In June 2024, Prof. Lei Li et al. (Sichuan University) built a GP LCL-based electric zoom system, which was designed with a super-resolution generative adversarial network11. In July 2024, Prof. Philip Bos et al. (Kent State University) delivered a 50-mm aperture, 1.6-diopter tunable GI LCL with a 28-segmented phase profile controlled by concentric ring electrodes12. In August 2025, Prof. Yi-Hsin Lin et al. (National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University) stacked two GI LCLs with their alignment directions perpendicular to each other, thereby realizing polarization independence13. In September 2025, Prof. Hak-Rin Kim et al. (Kyungpook National University) demonstrated a two-GP-LCL system in conjunction with switchable circular polarizers, which could support up to 9 focuses to vary the image distances from 26 to 333 cm14.

As summarized in Table 1, GP and GI LCLs are compared in the following aspects. (1) Type of phase to be modulated: geometric phase for GP and propagation phase for GI. (2) Form factor: both can be flat. (3) LC alignment: LC molecules in GP are aligned horizontally, whereas those in GI can be aligned both horizontally and vertically. (4) Maximum phase shift: GP is 2π, whereas GI can easily exceed 2π by increasing the thickness. (5) Focus tunability: GP is normally fixed, whereas GI can be electrically tunable. For GP to be tunable, a multi-lens system is needed. (6) Polarization dependence: GP can only work with circular polarizations, whereas GI can be polarization independent. (7) Wavelength dependence: GP is more sensitive to wavelength than GI. (8) Angular dependence: both are sensitive to angle. (9) Thickness dependence: GP must strictly meet the half-wave requirement, whereas the GI does not. (10) Manufacturing: GP is usually prepared via photoalignment, whereas GI via patterned electrodes. To our surprise, GI LCLs outrival GP LCLs in nearly every metric. That said, from a research perspective, GP has more scientific problems pending for investigation.

GP LCLs GI LCLs Winner Type of phase Geometric phase Propagation phase n/a Form factor Flat Flat tie LC alignment Planar Planar and vertical GI Maximum phase shift 2π 2π or above GI Focus tunability Fixed Tunable GI Polarization dependence Circular only Linear and unpolarized GI Wavelength dependence Strong Moderate GI Angular dependence Strong Strong tie Thickness dependence Strong Weak GI Manufacturing Difficult Easy GI Table 1. Comparison between GP and GI LCLs.

As to the question raised in the title, i.e., which is the ultimate LCL, GP or GI, it is still too early to tell. This is because we have yet to discuss the possibility of merging GP and GI into one single hybrid lens or a cemented doublet, in which both the geometric and propagation phases are exploited. For some unknown reason, the research on GP and GI has always been conducted separately. For researchers, who are pro-GP, they tend not to adopt any GIs in their designs, and vice versa. Hopefully, this situation will change soon.

We are witnessing a dramatic shift in the optical lens industry. At the heart of this transformation lies in the rise of flat optics such as GP and GI LCLs. While challenges remain, the rapid progress in this field indicates that they are on a clear path to becoming ubiquitous in the next-generation devices, e.g., augmented/virtual reality eyewear15–18.

HTML

-

Special thanks to Prof. Hak-Rin Kim (Kyungpook National University), Prof. Jianghao Xiong (Beijing Institute of Technology), and Prof. Dan Luo (Southern University of Science and Technology) for sharing their insights. Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China (GO0300164/001), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Municipality (cstb2023nscq-msx0465), Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (JZ2024AKZR0539), and Guangzhou Lujia Innovation Technology (25H010102931).

DownLoad:

DownLoad: